Aunt Melita used to live on Hall Street with her husband Ernest in a house where I spent a lot of summertime. Decades later, I don’t remember much of its architecture. I don’t remember the exact address. The house on Hall is instead a film reel. Any thought of it evokes the same, highly specific, hazily rendered scenes:

Cousin Arian in the living room summer after summer, watching and rewatching Stand by Me and The Goonies, two films I cannot say for sure I’ve ever watched, beginning to end, because they bored me so then that I’d wander off whenever he hunkered down in the living room to screen them. His dad, my Uncle Ernie, teaching an overgrown 11-year-old me to ride a bike in the back alley. Dozens of Page 43s torn from issues of Jet magazine arranged as a curated papering of Beauties of the Week on Arian’s bedroom wall. Uncle Ernie’s conversion van in the driveway, with a little TV in the dash. Arian and I in the kitchen, figuring out that this new brand of cookie called Keebler Soft Batch tasted better when heated for 7-10 seconds in a microwave. Uncle E’s face lighting with scary-campfire-story glee as he recounted, scene for scene, the 1980 film, The Elephant Man. Feeling so terrified of what he’d described that I later crawled into Aunt Melita’s bed and snuggled as close as I could in hopes that she’d be able to protect me when the elephantine monster I’d (erroneously) imagined showed up in her bedroom.

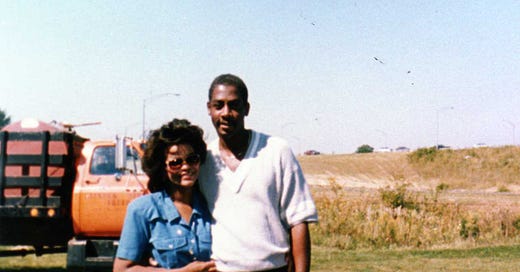

Aunt Melita and Uncle Ernie’s house on Hall was the first of the two they would own over the course of their life together. It was there where I first began to understand that, in Grand Rapids, Michigan, home would always be with them… even though the city also housed my father.

Aunt Melita and Uncle Ernie moved crosstown in the early ‘90s. The new house was in the northeast part of the city where, for at least a decade, they were the only Black homeowners on their block. It was a far cry from where Uncle Ernie was raised, in the historically Black part of Grand Rapids closer to downtown. A far cry, too, from Hall Street, which was also predominantly Black.

The outside of the house took some getting used to. Unlike Hall Street, where people who knew my uncle—a lifelong Grand Rapidian and former U of M championship-winning basketball star—would cruise by slowly and yell greetings from their car windows, the new neighborhood was eerily quiet.

Neighbors stared as they stood on their front porches, peeked out at us from behind their living room curtains and glared or ignored us while walking their dogs.

There was little community among lawns, though to the extent that any neighborly affinity could be found, Uncle Ernie cultivated it. He was fastidious about mowing in summer and shoveling in winter, dogged about raising a cool hand of greeting at grown folks in their yards as he cruised by in his black Caddy and affable with their kids, who craned their necks 6 feet and 7 inches to spot the smile on his face.

Inside, the new house felt far more akin to the old one. Its walls were painted in warm shades of peach or brushed with soft strokes of gray. Its rooms hosted years of family gatherings, namely Kwanzaa celebrations where our little ones lit the kinara and recited the seven-day principles. Every surface seemed to reflect the themes of Black love, Black family and Black art that had been present on Hall—and in Aunt Melita and Uncle Ernie’s hearts, lifelong. They were a couple who carried the full, lush power of their personalities into every room they entered, unfurling them like imported rugs and sleeping bags, ever making space for others to sprawl and rest, to be welcomed and warmed.

My father has lived in Grand Rapids for nearly as long as his sister and brother-in-law. He has lived in apartments of various types—rental house, basement-floor, duplex—in sundry parts of the city. Usually, he moved around with a large-breed dog of some sort. He has always favored Great Danes.

I was terrified of dogs when I was a kid. That became a convenient reason for us not to spend much time together at any of his homes. If I stayed over for a night or two, he’d have to board his dog elsewhere and taking time away from the dog for more than a few days, in order to spend time with me while I was visiting from out-of-state, always seemed like too high an expectation.

I still don’t care much for dogs, but I’m no longer very afraid of them. Still, when I pet one in front of my father, there’s always a moment of vocal surprise. “Oh, look who’s petting the dog,” someone will say, as though I’m not a 43-year-old fully woman capable of regulating her discomfort around animals. Intended or not, in those moments, it always feels to me like a reaffirmation of our distance: we cannot possibly be close if I’ll barely engage with what he most adores.

In truth, I moved past the worst of my cynophobia in my early teens. By then, though, Dad and I had made Aunt Melita and Uncle Ernie’s house our visitation hub. We watched movies together in their basement or Dad arrived on their front porch to take me to lunch and a theater then dropped me back there soon after a movie ended.

I’m grateful for the time he’s spared me. I’ve gotten more of it than some kids do, when they spend most of the year living hundreds of miles from their fathers. But I’m more grateful for the space my aunt and uncle gave us in their home to grow our relationship into what it’s become. Without the involvement of my father’s family, without the times he was able to visit me at his mother’s and sisters’ homes, we would not be even who we are to each other now: a father and child who share an interest in film, an aversion to conflict and an inability to clear whatever hurdles compel us to keep each other at arm’s length.

When I was 27, I was offered a teaching job in Grand Rapids. It was the end of the summer I matriculated grad school, two weeks before the start of the fall college semester and, because I’d long harbored fantasies of being a professor, I would’ve moved anywhere for the adjunct work a college might’ve given me.

I didn’t think much about my dad when I accepted the gig. I didn’t consider what it would be like to live year-round in the same city where we barely visited with each other during summers when I was a kid. It didn’t occur to me, the emotional chaos that had the potential to cause.

The first call I placed was to my aunt and uncle, who immediately invited me to stay with them until I could afford a place of my own. My next call, the one to my dad, came with congratulations and a question: “Who will you stay with, Melita and Ernie?”

When I moved in with them, none of us understood how little adjunct work paid or how long it would take me to build enough savings to make rent every month.

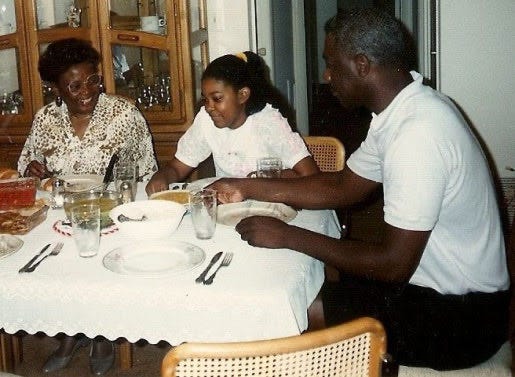

I was with Aunt Melita and Uncle Ernie for three years before I got my own apartment. While I was there, they drove me to bus stops in the dark when I was teaching an early-morning class. They drove me all the way to Allendale when it was too frigid or icy to ride the bus. They treated me to countless restaurant meals, because they maintained a ritual of eating out at restaurants and wouldn’t dream of excluding me, even though I couldn’t afford the extravagance. They taught me to drive (along with my dad) and recommended the dealership where I got my first car. They helped me organize that apartment when I finally got it. And when I got pregnant one month after moving in, they accompanied me to months of prenatal appointments so I wouldn’t have to attend them all alone.

I’d always felt close to my aunt and uncle but never so much as when we shared their home. Living with relatives as an adult is always an education. It is an observation in intimacy, a negotiation of resources that are not your own, a calculus that must account for when you’ve overstayed your welcome. For all three years, I felt the dull ache of discomfort that comes from knowing that you’re living in space that doesn’t belong to you, that you aren’t contributing nearly as much as you should to the household’s upkeep, that you should be a self-sustaining adult by now. But they never made me feel like I’d been with them too long (even though I very clearly had). Instead, they made me feel like I belonged with them.

When Uncle Ernie died suddenly five years ago, I was living back in Baltimore. My father was the one who called to tell me. When I hung up, I let out a sound unlike any I’ve heard before, a hollow yelp that strangled itself in my throat, as if attempting to suppress the sound would make the reality causing it go away. I flew out with my daughter the next day and was back at the house in Grand Rapids by the next sundown.

Our whole family seemed to be crowded there, trying to keep Aunt Melita reassured that she would somehow be able to walk through a world that didn’t include the husband with whom she’d shared 37 years.

But we knew our reassurances were inadequate, because we’d tried them out first on ourselves. We were all unsure that we’d ever figure out how to do it. The panic and pain—emotions their home rarely caused or carried—were palpable.

I am in Grand Rapids now. I’ve been here nearly a week. It’s the first time I’ve been able to return since 2019, just before the pandemic. My daughter and I are here, in part because Aunt Melita had a hospital procedure scheduled and we wanted to be here to support her.

Every time I’ve returned here after Uncle Ernie passed, I’ve done it with him in mind. I try to show up in ways that reflect him. I try to be for my aunt who he was for me. I try to reflect his love back to her, along with my own. Because I knew. I saw up close and I knew how carefully he loved her.

I think most, whenever I visit, of those three years their home was also mine.

Whenever we’re back now, my daughter walks through every room, itemizing and voicing aloud the observations of change I also quietly track; the house looks a lot different than it did when a couple lived together in it. Now, it is the abode of a woman who lives on her own. The man-cave the basement once was has become what my aunt calls a “she-den.” The kitchen has been remodeled. Several rooms of the house have been restyled.

But it’s clear that Aunt Melita left room here for her husband; even with all the renovations, his presence is still felt in every corner of their house.

When you make a home of a person, they will remain, as long as you do, in the home you made with that person.

I haven’t seen much of my dad this week. He hosted a picnic in a park the day after my daughter and I arrived. We spoke and hugged and I took two beautiful photos of him and my daughter. It was good to see family; it was a balm. But it was bittersweet, too, in ways I can’t yet describe.

I saw my father for about five minutes the next day, too, and I’ll see him again when we leave for the airport, as he’ll be driving us there.

I don’t know whether we’ll spend a moment of one-on-one time together. I don’t know whether or not it will be another four years before we lay eyes on one another in person again. And I am not as resigned about either of those things as I am working hard to appear to be.

But every day that I’ve been here, I’ve felt entirely at home. Every day that I’ve been here, I’ve been with my aunt in the home she (and I, for a series of magical summers and a generous pocket of years) once shared with my uncle.

It’s hard to imagine any outcome more fitting than that.

Bonus Photo:

Stacia, I love your writing so much. Always have. What a treat to have even more on the regular! I will upgrade to paid sub when I can. You inspire. Much love to you and story. p.s. God bless your Aunt and Uncle. 💜🎵💜