Aunt Smuckie's green-shingled house has two enclosed porches. Historically, each portal has conveyed distinct intent. If you were coming over for a real visit–if you were like me as a child and you were meant to spend multiple nights, or if you were planning on a true sit, to share tea and cigarettes or listen to records or talk for hours while BET-edited versions of Black classic movies played on a TV in the background–you knew to pull into the gravel driveway on the side of the house, to hook a quick right and walk up the steps to the back porch, where the inner door was often open in the summer, so that your approaching footsteps could be heard through the screen. The crunching pebbles were an announcement under your soles, and often, a diminutive silhouette would appear in the doorway, unlocking the screen before you even had the chance to knock.

If you were just stopping by--if you were an acquaintance or postal worker or stranger--you parked on the street and politely rang the front doorbell. The front door was usually closed, so that no movement could be seen inside as you approached the house. Though Aunt Smuckie was almost always at home, you'd have to open the outer door and keen your ear toward the inner one, to see if you could make out the shuffling of slippered feet. Sometimes you couldn’t. On rare occasions, she actually wasn’t on her way to see who was ringing her bell. But more often than not, you could hear her familiar footfalls and soon, you'd hear the tumblers of that front door unlocking, too.

Of course, if you were blood, you could come to either porch. Sometimes you'd just find yourself riding down the quiet rows of mostly Black-owned homes on her block of Wall Street and you'd pop in on her just because it was polite to do so if you were passing by. If family rang that front bell, it signaled that we did not intend to stay. We were just paying our quick respects while running an errand or heading on home. Aunt Smuckie would then lean outside the front door and chat with you awhile or, on rarer occasions, if that chat ran too long, she’d invite you into that liminal space that was the front porch, where baskets of decades-old Jet magazines sat under a series of covered seats. You might linger there for a bit but you would not sit. Despite its deceptively inviting decor, the front porch wasn't really for sitting.

Besides, if you made it that far inside the front of the house, you might as well pull around back and park.

In my memory, Aunt Smuckie's home is recollected in stages. When I was a child, she lived there with her husband. They would've been in their late 40s or early 50s then — not much older than I am now. Uncle George was brawny and bald and reminded me a bit of a dark-complexioned Mr. Clean. He smelled of motor oil and worked on cars and other things that needed fixing, mostly out of their detached garage behind the house. But he also made house calls, all around the city.

Uncle George kept a barrel smoker in the backyard and was known as one of the best barbecuers on his side of Jackson, Michigan. Aunt Smuckie was petite with an impossibly tiny waist. She wore slacks and blouses almost exclusively. Dresses and skirts were only for particular occasions. She smelled of perfume and nicotine and, in those days, her hair was pressed and curled into a soft, short roller-set style that perfectly framed her face.

Aunt Smuckie had a bit of a strut to her. She'd hook the straps of a pocketbook on her inner forearm and saunter her way through a door with a surety that let you know she'd arrived. Her eyes held a glint of mischief. A smirk often played on her lips and before she would even take a seat, she’d dash off a quip so wry, you’d smile before you’d even processed the punchline.

It was easy to see what might’ve drawn my uncle to her years before. She was pretty, but perhaps more importantly, she was as smart and as quick as a flicking whip.

They were a striking neighborhood couple, Aunt Smuckie and Uncle George.

When I spent summers in Michigan during elementary school, I often stayed in one of their two spare bedrooms when I wasn’t at my great grandparents’ house. Like everyone else who took me into their care during the summer months, they treated me like I was supposed to be there, like it needn’t even be a point of discussion. But it felt a little strange being there nonetheless. Their home was filled with what looked like carefully curated spaces: the living room with its cream and rust-tapestried furniture, statues and busts either of a lone woman crouched pensively or a bronze couple frozen in a passionate embrace, trinkets strategically placed on the surfaces. Coffee tables and lamps too fancy for a child to relax around. We were not meant to spend much time in the living room.

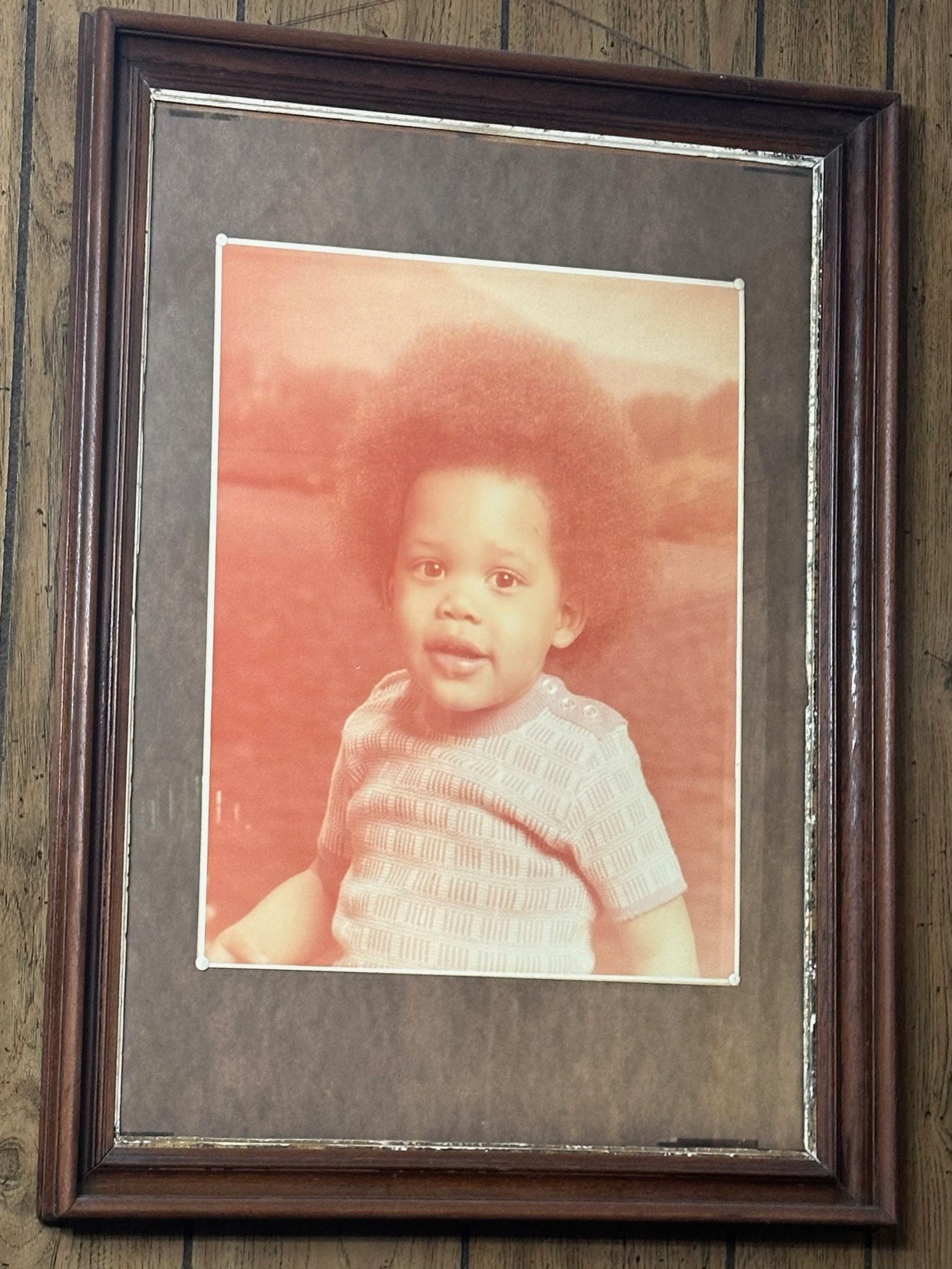

Mostly, we visited in what I always considered to be a dining room (though we never dined there during my visits). There was a chifforobe in that room, a cherry wood table with sides that folded down and a massive framed picture of their firstborn grandchild Cedric hanging on the wood-paneled wall.

That picture could transfix you with its sepia tones, the chubby cheeks of a boy in toddlerdom whose massive, leaping ‘fro filled a near-third of the frame. Cedric’s was the only family photograph I remember being displayed. But of course there were many others. They were just so much smaller. Dozens of family photos filled the rooms, each in a frame of its own, tilted just so on surfaces throughout the house.

There were two sets of stairs in the house. The ones off the living room led to a bathroom at the top of the stairs and three bedrooms, two on the left, one on the right. The farthest room on the left was the master. I remember it as very white, from the walls to the bedding to the headboard with the bookshelves to the dresser with the vanity mirror. Aunt Smuckie had jewelry boxes; she loved gold accessories. Sometimes she’d riffle through them and hand you something to keep.

If you were a woman or girl staying over, this floor was your obvious appointment. But if you were a boy or man, you might spend more time descending the other set of stairs, the ones off the kitchen that led to the basement. The basement was Uncle George’s domain, a man cave before we knew that phrase for it. I remember it as impossibly dark, even during the day, though it had tiny windows that sat above ground, so that small rectangles of light did shine through.

At the bottom of the basement stairs was a wooden door with a metal hook latch. When I was a kid, I might find it either open or closed. If it was open, it meant that Uncle George was fixing things, as it was his repository for tools and supplies. He had his own furniture down there, his own hi-fi with a built-in 8-track, his wall hangings and statues. A half-bath, so he needn’t make the long trek to the second floor of the house to reach a restroom.

The only time I knew Aunt Smuckie to go down to the basement was to do laundry or to retrieve meats and sundries from the deep freezer next to the washer and dryer.

We kids could explore the basement during the day, but only if Uncle George wasn’t at home. It was off limits to us if he was. Sometimes we were dispatched to call out to him from the top of the stairs but we were not permitted to go down. At least I wasn’t. I can’t speak for the boys and the men.

Spending time in the basement made us feel like we had our own apartment, like we were little sophisticates, raising ourselves, sharing our little secrets in a space we believed was too deep and dark for them to be heard.

There was a kind of magic to other people’s homes when you were a child. Every space felt more mystical because it was not your own. You could stare at every trinket, examine every bit of decor, snoop through the kitchen cabinets at all the snacks foreign to your own household, peer down into trays of ash and cigarettes butts ringed with lipstick. You could open a refrigerator door and tilt your head in curious wonder at the precarious arrangement of provisions on each shelf. You could flip through the pages of trade paperbacks—westerns and romances and Black arts movement titles, both fiction and non-. And you’d think: This is a whole other life. What must it be like to inhabit it?

Sometime between my teen years and my early 20s, Uncle George had one stroke, then another. An elaborate ramp was added to the front of the house, so that on the rare occasions that Uncle George would leave it, Aunt Smuckie and her son Delbert could maneuver Uncle George’s wheelchair down to the sidewalk with ease.

We all, at some point or another, walked that ramp if we approached the house from the front. The walk was a sober reminder of how significantly life had shifted for the couple living inside. By then, both Aunt Smuckie and Uncle George were disabled. Sometime before the strokes, Aunt Smuckie had a tumor removed that left her with deeply impaired vision.

Over time, she began to walk with a white probing cane when she left the house. Both she and Uncle George needed to be driven by relatives to their appointments. Family, neighbors and friends ran their errands and did their store runs. They could no longer keep up with the formerly bustling goings-on in the backyard. Gone were the days of barrel-smoked barbecue. Their cars were eventually absent from the garage; driving had long become a thing of the past. And the house was much quieter on the whole, as the strokes left Uncle George largely non-verbal while Aunt Smuckie’s legal blindness, as well as the demands of caring for her ailing husband in-home, rendered her life more somber than I’d ever remembered it.

Visits were more morose, too. Aunt Smuckie’s wit was as sharp as it had ever been, but the demands of the illnesses suffusing her home seemed to hamper her humor’s natural levity.

Or maybe it was just the effects of growing up. Maybe it was the growing infrequency of my trips back to Jackson. I was there far less after I turned 18. Annual summer visits were a thing of the past.

When you’re a child, you never think about the logistics of being “sent to family” for the summer. You don’t think of the cost or the time commitment. Those are not yet your own expenses to carry. You don’t notice the restriction of movement you may feel as an adult spending extended, car-less time in a town it can feel hard to leave, even when you have your own transportation.

There is an invisible pull in Jackson, a gravitational tether to the past, an acquiescence to others’ expectations. You can only feel free there once you’ve learned how to sever it. But severing the tie you feel when you’re in that town leaves you lonely whenever you spend time in it. Jackson is not a place where it is very easy to be your own person. Some might argue that that’s for the best. Every Black person there seems to know one another. News about your life, whether good or bad, travels faster than you can catch it. Plans are made for every minute of your time there before you even cross into city limits.

At 44, I can locate the beauty in that, the intimate familiarity that stretches from one end of town to the next. The way nothing there, whether good or bad, ever changes so much that it becomes unrecognizable.

At 25, though, when our family matriarch, my great-grandmother Verlia died at 95, and in all the years that followed, when there was no more “family home,” no nucleus or need to fit in as many visits to our oldest living relative, it grew harder to imagine returning to the town it was no longer prescriptive for me to visit.

I did not consider that Grandma Verlia’s daughters, my nana and Aunt Smuckie among them, were not getting any younger. Like their foremothers, quite a few of the women in our family live long and active lives. They are sturdy and stalwart, almost omnipresent in the imagination.

You think you’ll have time.

During my late 20s, I lived in Michigan for four years. Not in Jackson, but rather on the western side of the state in Grand Rapids. I got back to Jackson a few times during those years, but it was usually for funerals. We lost a lot of people in the aughts. Uncle George passed in 2006. My cousin Lynette in 2009. My aunt Sharon in 2010. I was expecting during those last two homegoings. I’d discovered it days before my cousin’s homegoing. At Aunt Sharon’s I was four months along.

I came back, too, for my cousin Marcia’s baby shower. She was a few months farther along; her baby was due in May 2010. Story was due in late July. I came back again in 2011 for my cousin’s daughter’s first birthday party. Then, for the last time, for my own daughter’s party.

Story had two first birthday celebrations, one in Grand Rapids with my father’s side of the family and another in Jackson, with my mother’s side.

It was a good day, albeit an exhausting one. I’d flitted from one side of town to the next buying tiaras and wands, foods and favors. Many hands made the work light. Cousins helped us cook out and pick up the sheet and smash cakes. Someone kept the music going. Someone else entertained the kids when they tired of entertaining themselves. We all looked after the elders, making sure they had some shade on the sweltering August afternoon, fetching them ice cream cones to stave off the heat and plates when it was time for a full meal.

I remember the day well. I have always remembered that day well. It was the last one I would spend in Jackson for 12 years.

It is fitting that Aunt Smuckie’s passing was what would bring me back there. Before the last weeks of her life, she and my nana, two years apart in age, spoke on the phone multiple times per week for most of their 80+ years of life. If my daughter was in the room, Nana would put her on the phone. She spoke with Aunt Smuckie far more than I did. The two older women would chuckle over the silly, precious things my daughter said.

This was the only way my daughter knew her, as a kindly, aged voice wafting through a landline phone. That niggled at me but not enough to get Story back to Jackson. There would be time. When I finally found a full-time job, for instance, when I could afford to make the trip on my own terms. If I found myself elsewhere in the state, visiting the other side of our family, I’d think as I flew back out of town (on tickets my paternal aunt helped me and Story afford): I’ll get over to Jackson next time.

And then, when I moved further south from Maryland to North Carolina, the trip felt even more daunting, the distance seeming much farther.

As it turns out, it is a 10.5-hour drive, through Virginia, West Virginia and Ohio to Michigan. It can be done in a day, twice within three days, if you’re motivated.

I rented a car and left Sunday for Aunt Smuckie’s Monday afternoon service. On Sunday night, we checked into our hotel then hopped back into the car for the wake. After that, we found ourselves back at Aunt Smuckie’s house, to pay our respects to her son, who was receiving visitors there.

The house, now his, looked different on approach, but only because it was so open. I could see people milling about inside, their silhouettes fully visible through the open door. One of Aunt Smuckie’s grandsons was sitting on the front porch. Unsure of the rules, now that they had changed, I asked, “Should I close the door behind me?” He said I could leave it; he’d close it if need be. The couches in the living room held multiple visitors. A small flat screen TV was there, a sight I thought I’d never see in the living room that had rarely been used for entertaining.

But more surprising than the things that had changed were the many things that had not: the chifforobe and picture of Cedric on the wood paneling; the cantaloupe, watermelon and grape-bunch magnets in the exact spots on the fridge and freezer doors where I’d last seen them decades before; the black rotary phone on the kitchen wall; the wooden fork and spoon set and wicker fans in the breakfast nook; the basket-bearing woman on the floor, sometimes used as a doorstop for inner back porch door; the lighter shaped like a can of Orange Crush sitting on a counter in the basement, the inexplicable wall tapestry of two dancing white folks hanging on a wall down there, that hi-fi with the built-in 8-track, that metal-latched wooden door.

It was uncannily different and eerily all the same. Aunt Smuckie was gone. Aunt Smuckie was also everywhere.

Story walked from one room to the next, gleefully absorbing each scene. “This is exactly like I imagined it,” she said. “All the houses here look like they’re from the 1940s!”

She wanted to see everything, the upstairs too, but given its most recent use for hospice care, it wasn’t open to company.

“I wish we’d come here sooner,” she lamented.

I watched her cut the same paths I had at her age and younger, from breakfast nook to kitchen to dining room to living room and back to the front porch. I watched her face light up whenever a new cousin greeted her. I felt her crowd-leery grip loosen on me over the course of the 40 or so hours we spent in town. I heard two adult cousins ask her to put their numbers in her phone, so they could keep in touch, whether I was inclined to answer my phone on a given day or not.

“Yeah… we can cut out the middle man,” Cousin Chelsea quipped.

It was clear to me then why Aunt Smuckie had so often wondered when I was going to bring Story back there. It was for all the expressions of love and attention she was missing, all the exploration of welcoming family homes she was being denied. It was the work that needed to be done before she grew too old to appreciate its value, while witnessing the way her relatives lived still felt like something magical.

I should’ve done it sooner.

This was gorgeously written Stacia - you paint such a compelling picture of Aunt Smuckie and her home. I love reading tributes like these of ordinary people who are extraordinary to the one doing the writing who loved them dearly. It helps me remember the things that matter, and that my legacy doesn't have to be grand or dramatic - it's likely that most of us will be remembered for many small things, and for the love we gave to those around us. I also appreciate how you grapple with the tension between the things you appreciate, and the things you wish had been different. It's a tension I feel about moving far away from my family too.

We had the same Lino in our kitchen as the stuff under the basket lady! You painted Smuckie’s home so vividly. It has me wandering thru my grandparents’ homes in my childhood mind.

This is a beautiful tribute to family, loss.