summers, pt. 1.

Growing up, I never spent summers at home. Within two weeks of school’s end in Baltimore, I’d find myself nestled into the window seat of a plane bound for DTW or stretched, sidelong and unbuckled, across the the backseat of a relative’s car, headed 10-12 hours north to Michigan, where I’d spend 6-8 weeks in several households across to 2-4 cities in the southern and western parts of the state.

My maternal great-grandparents, George and Verlia, lived in a house with yellowish-tan siding on a sleepy street in the small town of Jackson. The house always looked small from the outside, with its front lawn consisting of two patches of grass and a lone pear tree on its right side (I think there were more trees in the back).

But somewhere on the short walk from the graveled driveway to the enclosed front porch, between the creak of the outer screen door and echoing trill of the bell at other other (if it wasn’t unlocked or open already), I’d remember: Grandma and Grandpa's house was a kind of Narnia, opening into an ethereal expanse where there was, somehow, always just enough room for whoever might show up and need it.

There were three bedrooms crowded at the top of the narrow stairs, and another just off the dining room on the first floor. The living room comfortably sat about five people but there tended to be many more, perched on several steps of the staircase, leaned against the arm of the LazyBoy, piled two per cushion on the couch, with folks gingerly positioned on each other’s laps. The TV rarely left whichever channels were broadcasting baseball or the local news.

Grandma’s kitchen could hold 12 people or more people—and often did, between the extra chairs pushed in at the long dining table, folks prepping hot plates at the oven, aunts washing an endless queue of dishes at the sink, uncles pulling French vanilla ice cream from the upright deep freezer, cousins slicing liberal chunks of pound cake from a tiny dessert table, Grandma grabbing fresh butter from the fridge.

Grandma Verlia was tiny, a diminutive 5-feet-even, if that. It could be hard to believe she’d borne 11 babies and raised the 10 who lived. It was when I crossed the threshold of her kitchen, where activity was efficient and supply seemed unending, that it became entirely plausible.

Most of my summer visits to Michigan began at Grandma and Grandpa’s. I’d be the only kid staying there. My great-uncle Warren lived upstairs. Grandpa stayed on the first floor. Grandma and I slept upstairs. Sometimes they’d let me have cousins over. Other times, they’d let me sleep over at their houses. But they were generally understood as my custodians for as long as I was in town. Theirs was the number my mother dialed when she wanted to reach me. Theirs was the door I was delivered back to when it was time to go visit my father’s family.

Like Grandpa and Grandma Verlia, G-Mom, my dad’s mother, had come to Michigan from Mississippi. The former had come from French Camp and thereabouts in Choctaw County. G-Mom, the only girl of several brothers, had come from Natchez. Where the former settled near the bottom of the Mitt, the Travises, my dad’s family, managed to find themselves in Muskegon.

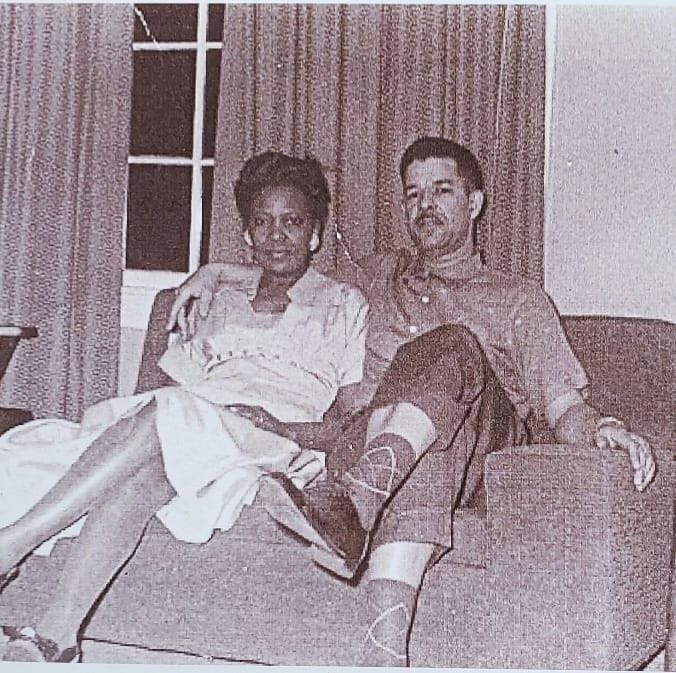

For decades before I was born, G-Mom had a husband who looked a bit like a movie star. All old photos suggest they cut a handsome figure, with their four cherubic children, immaculately manicured lawn and frequent family trips to do outdoorsy things like camping and fishing.

G-Mom’s husband, my grandfather, died a month after I was born. Perhaps because of that timing, I spent a lot of time at G-Mom’s house in my earliest summers. She let me sleep in her bed until she remarried and then, because I was afraid to be alone upstairs, I’d sleep in her living room. Of Muskegon, I remember the milkman. G-Mom was still having her milk delivered in the ‘80s, a practice I’d never seen outside of black-and-white sitcoms on Nick at Nite. I remember the hammy smell of the paper mill, the almond extract G-Mom used in her poundcake, fresh-baked blueberry pies. Shared baths with cousins. Wheat bran sprinkled onto everything (for regularity). The astringent sting of Dr. Tichenor’s for cuts. Birdwatching in the backyard. Ping-pong in the basement. Boxing matches on TV at night. Bedding down while the sun was still up.

To combat my potential loneliness, G-Mom tried to coordinate visits from my cousin Joe in Chicago to coincide with the weeks I spent with her. From there, I’d fan out to Grand Rapids or Kalamazoo, where my aunts lived with their husbands. In Kalamazoo, there were Aunt Bonnie and Uncle Bob’s four kids to play with. In Grand Rapids, there was my cousin Arian who, like me, lived in the northeast and only traveled to the Midwest in the summer. He looked exactly like his dad, my uncle Ernie: tall and lanky and elegant in every movement.

Perhaps the most consistent peer socialization I had, outside of the eight childhood years I spent attending church with mostly the same set of kids, was during those summer months with my cousins of similar age. I learned from them that conflict could not be avoided, that reconciliation could be easy, that colorism, texturism and featurism exist (though the names for each would come to us much later), that in families, there will always be favoritism, whether openly acknowledged or denied, that I would benefit from some of those -isms and suffer for others. From them, I learned that, for as long as you’re together, you don’t leave each other alone.

Adult summers have been different. I stopped regularly showing up in Michigan when I graduated from high school, the necessity to keep me occupied and supervised without summer camps having disappeared with the advent of college. Grandpa and Grandma Verlia passed long ago. G-Mom’s also been gone for over a decade and, before her passing, she spent her last 8 years living with Alzheimer’s, so it has always felt like I lost her much earlier. I can’t say that my cousins and I know each other very well as adults. My daughter hasn’t barely knows their kids at all.

School dismissed for her two weeks ago. She tends to spend her summers with me and with her father. We put her in summer camps sometimes, but often she’s at home with one of us.

Yesterday, we left our half-unpacked new apartment, shoved a few suitcases in the back of my Santa Fe and headed up to Maryland. I dropped her off with her dad before continuing on to Baltimore. I’m writing this from my Nana’s couch, still tangled in the bedding she made up for me here.

I’m struck this morning by how different her summers have been from the ones I spent up north as a child, how different her experience of home must be. I worry over what she’s missing, even as I understand that what I had in those varied summer homes—the love, the longing, the lessons—doesn’t exist anymore. It cannot be replicated for her and I’m not sure that I’d want that, even if it could. The airlines I flew have folded. Milkmen are extinct. The elders have long been ancestors.

And for her, a mother isn’t someone you fly away from in June. A father isn’t someone you hope to find in the homes of his sisters and mother in July. For her, parents are people you run to. They take you to their Narnias, help you navigate dynamics there that long predate you, boost you up the labyrinthine branches of your family trees, bring you back home with ancient answers to all your new questions.

I hope that we are home for her, that wherever we are, she feels emboldened to explore more of who she is, and that when she is old enough to go it alone, she understands that she will never have to.

In two days, I’m taking her to visit my dad’s family for the first time in about 4 years, our first foray into post-pandemic air travel. We will see aunts, uncles, some cousins. I’ll help her keep everyone’s names and she’s straight (likely by asking someone else to help). We’ll fly back, and I’ll drop her off again with her dad. Before long, he’ll return her to me. Between the two of us, all summer, she will have never left home.