a sonic bequeathal.

in memory of michael eugene "d'angelo" archer, 1974-2025.

He never wanted much to do with us. Not before he bared half his body, onscreen and on tour, and not after. He withstood a spotlight, rather than basking in it, debuted in a brown leather jacket, delighted in artful obfuscation, shrouded himself in so many garments, it could be mistaken for sartorial mummification.

He wanted to disappear, into melodies and meaning, away from our insistent eyes, our wanting, impatient ears. Even the lyrics were muffled, under the weighted blanket of his mouth.

If we were meant to hear, we would have to work for it.

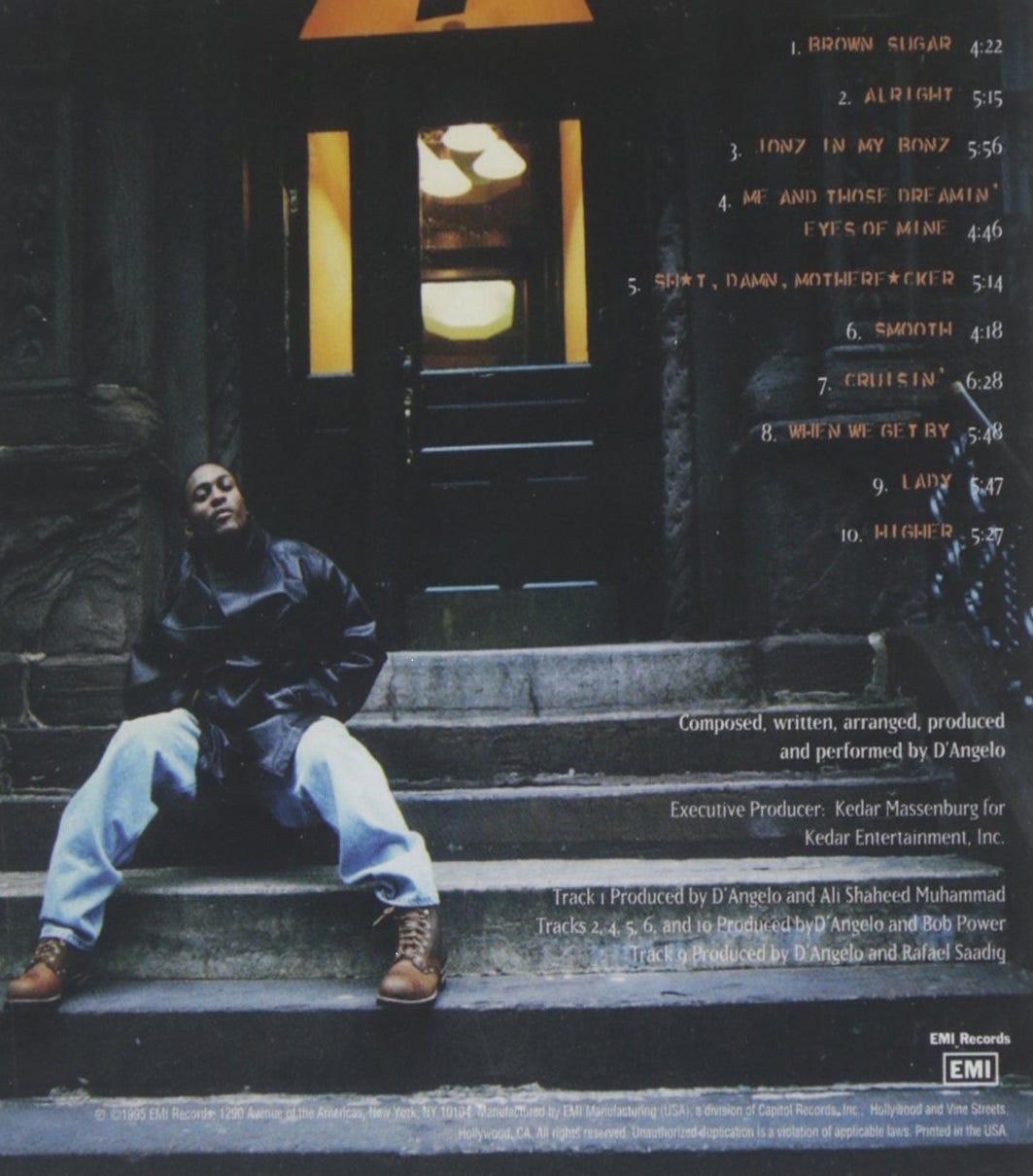

D'Angelo was as reclusive as his music was relatable, as sophisticated a songwriter and composer as he was a symbol of soul and, for the briefest of eras, of sex. He was my bedroom-poster crush when I was 14, the summer when Brown Sugar dropped, when the watery dreamscape of “Jonz in My Bonz” floated through my Discman headphones, when I force-skipped “Sh*t, D*mn, Motherf*cker” because I was still in the throes of the guilt-inducing churchiness D’Angelo himself was shuffling off as he penned that single around the age of 19.

By the time I turned 19, I couldn’t listen to “Lady” without being reminded of the four-years-older first boyfriend I’d just broken up with. Couldn’t pull my eyes from the four D’Angelos onscreen whenever “Me and Those Dreamin’ Eyes of Mine” looped on Video Soul. Fantasized about walking down the aisle to “Higher.”

I pulled that debut album over and around myself like a lover’s hoodie, always listening to it alone. Intimately. The way it was made. The way it was intended.

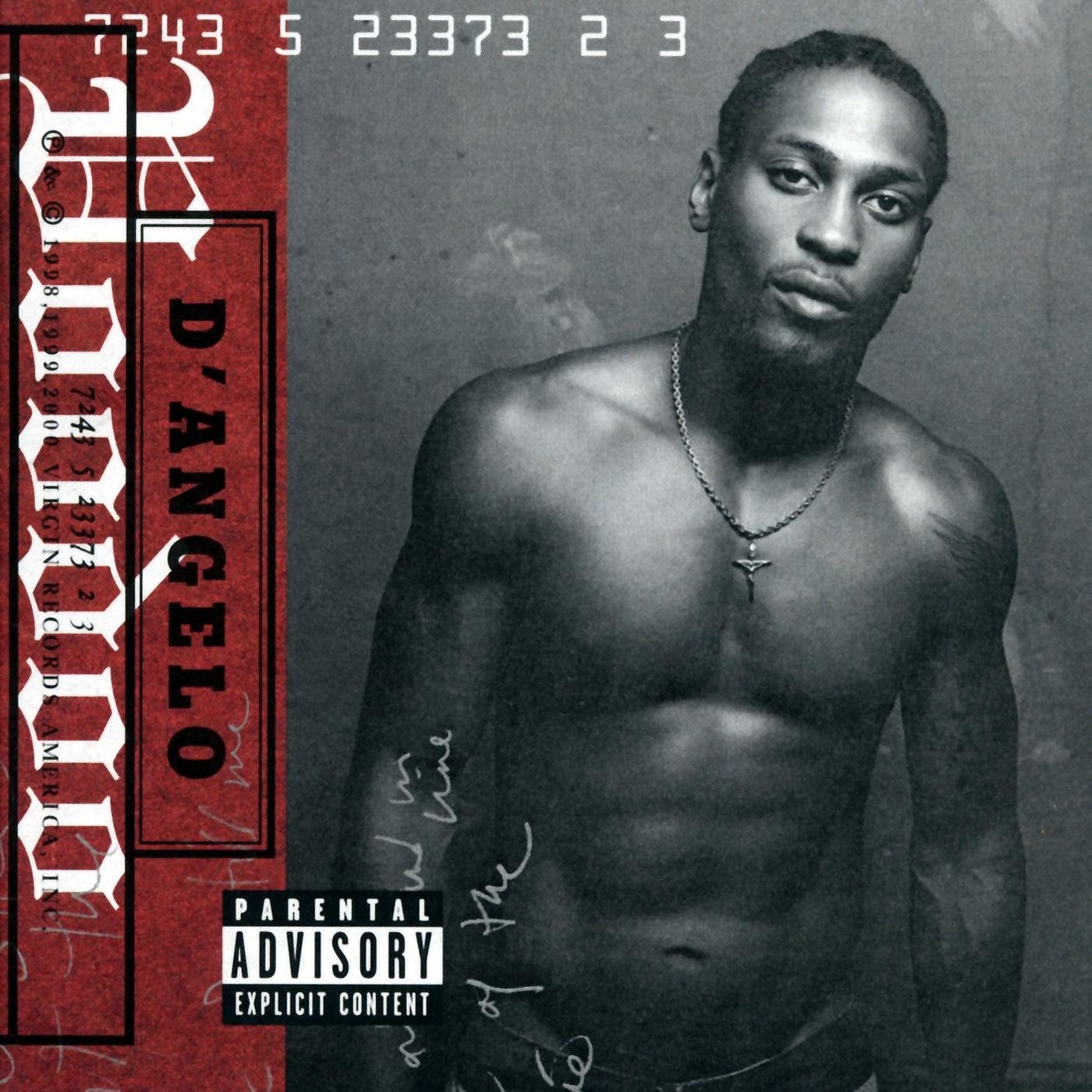

My junior of college, I rode the yellow line to Sam Goody at Greenbelt Mall to buy Voodoo the week it dropped. Still a church girl raised to be deeply suspicious of anything resembling the worship of non-Judeo-Christian spirits, the journey felt like a mission to obtain contraband. When I plucked the compact disc from the display stack, he was staring out at us, bare-torsoed, from the cover, with eyes that read clearly: I see you and lips upturned just perceptibly enough to convey: you will never quite see me.

My religious superstitions precluded any unfettered enjoyment I might have experienced with that album. Between its title, the title of “Devil’s Pie” and the collective, orgasmic hypnosis “Untitled (How Does It Feel)” into which all listeners descended (… ascended?), I worried, at 20, that getting as deeply entrenched with Voodoo as I had with Brown Sugar, would somehow lead me astray.

So I took pulls of “Spanish Joint” for a quarter-century. I embraced “One Mo’ Gin” as a transmutation of longing. I came to mark the possibility between an artist’s sophomore album and his debut in D’Angelo distance: a sonic measurement of maturity, anguish and exploration, an equation so many find impossible to reconcile, a solution involving reflection, self-protection and incalculable growth.

There were always rumors whirling in the chasm of his absence. A leaked track that eventually made its way to the third album. Whispers of James River. Infrequent, if eager, incantations of D’Angelo is the studio. D’Angelo is back in the lab. Speculation involving addiction, illness and recovery. Hushed hopes for good health in the years that bore no word.

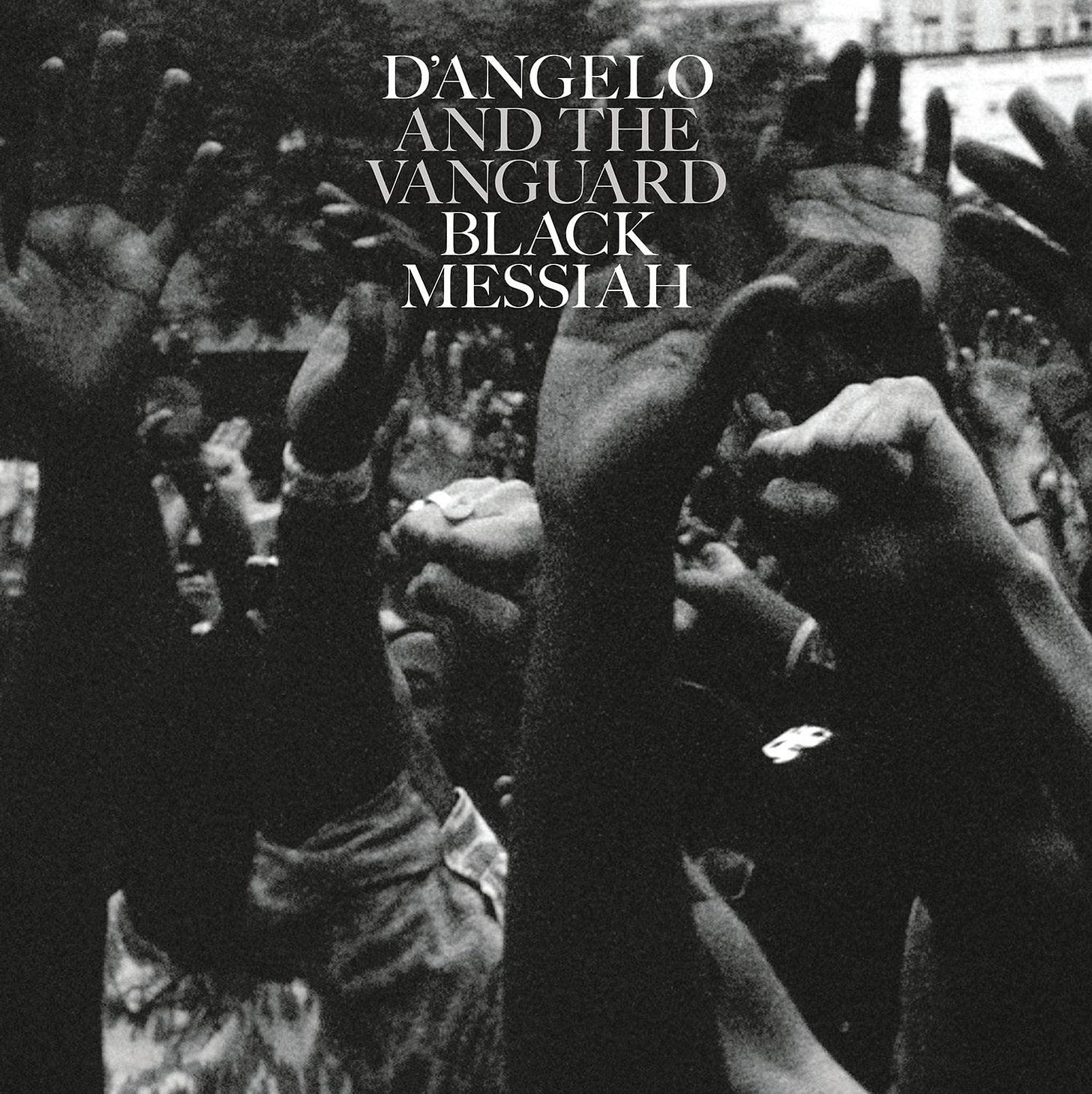

Then the third coming, an ultra-rare reemergence, a transmission from another realm: Black Messiah in 2014. It may not have come when we wanted it but it was, indisputably, right on time. In the year of Eric Garner. Michael Brown and the subsequent Ferguson protests. Tamir Rice. Akai Gurley: “The Charade.” The public exposure of the Flint water crisis: “Till It’s Done (Tutu).” When the audience who’d grown up alongside him were grown enough to be earning lasting commitment (“Really Love”) or losing it (“Betray My Heart,” “Another Life”). He appeared just long enough to reassure us that he living in tandem with us. And understood.

He was grappling with his own mortality (and ours) then.

He was grappling with his own mortality (and ours) then.

He was barely 40.

Eleven years later, almost as long as we had trained ourselves to wait for his albums to incubate, he is gone. Or rather, the parts of himself he never consented to share us are gone.

D'Angelo was, perhaps, the most decisively, intentionally private R&B artist of our generation.

He has bequeathed us exactly as much as he intended for us to have. We are still as close to him as we will ever be. We’ve acquired far more than we were entitled to, more than we deserve, more than we are given by most.

I just hope he understood there were so many more of us than there were of them. We understood. I hope he left this earth knowing how integral his sound and his privacy was to us.

Just resubscribed. I lived in Staten Island when Eric Garner was murdered. As I left the ferry to walk to our apartment on the North Shore, I was often approached by people selling loosies. I’d just smile and say I don’t smoke. At no time did I ever feel threatened by anyone.

I once marched with his daughter, Erica Garner, who fought so hard to exonerate the memory of her father, she herself died by not looking after her health. This, after an outlawed choke hold was used by an NYPD outlaw, and then set free by the outlaw DA.

I was not familiar with his music, but have since downloaded some songs on my phone.

Hope you are well in this horrible timeline. 🙏